Repository of Practices

DEMIG-QuantMig Migration Policy Database

Secondary GCM Objectives

Dates

Type of practice

Geographic scope

Regions:

Summary

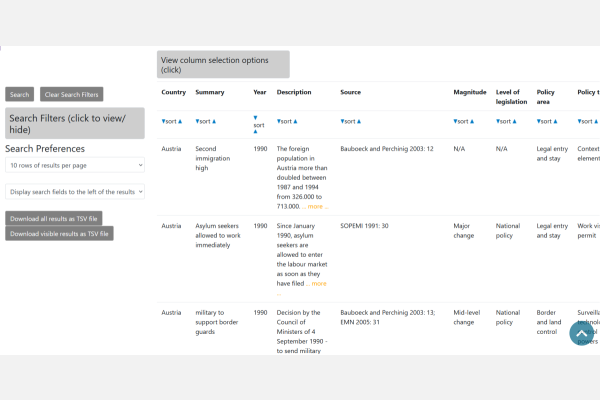

The DEMIG-QuantMig Migration Policy Database tracks more than 7,600 migration policy changes enacted by 31 European (EU and non-EU) countries for the period 1990 to 2020. This database extends and updates the DEMIG POLICY database developed at the International Migration Institute (https://www.migrationinstitute.org/data/demig-data/demig-policy-1) and follows the same methodology. The policy measures are coded according to the policy area and migrant group targeted, as well as the change in restrictiveness they introduce in the existing legal system. The database allows for both quantitative and qualitative research on the long-term evolution and effectiveness of migration policies.

Credit for the development of the original DEMIG framework goes to the International Migration Institute, Professor Hein de Haas and his team. For methodological details, please see: H de Haas, K Natter and S Vezzoli (2015) Conceptualizing and measuring migration policy change. Comparative Migration Studies, 3: 15, DOI: 10.1186/s40878-015-0016-5.

Disclaimer: This practice has been funded by the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No. 870299 QuantMig: Quantifying Migration Scenarios for Better Policy. This document reflects the authors' views and the Research Executive Agency of the European Commission are not responsible for any use that may be made of the information it contains.

Organizations

Main Implementing Organization(s)

Partner/Donor Organizations

Benefit and Impact

Key Lessons

(After: White Paper on Migration Uncertainty, https://bit.ly/migration-uncertainty)

Recommendations(if the practice is to be replicated)

Policymakers should be aware that for host countries, periods of uncertainty in migration policy encourage foreign residents to leave and discourage would-be migrants from coming. Policy interventions on migration flows often produce unintended consequences and side effects. Policymakers must consider the impact that some instruments may have on policymaking processes in other realms and in proximate countries.

in setting policy objectives, different priorities across various areas of government need to be taken into account and openly reconciled. Migration policy needs to be driven by a particular purpose, and be accompanied by honest communication about uncertainty, to improve preparedness and the understanding of migration and its impacts. Policy solutions need to be future-proofed by design, with regular update points and forward-looking exercises becoming part of the ‘business as usual’ routine, to avoid pivoting towards status quo.

(After: White Paper on Migration Uncertainty, https://bit.ly/migration-uncertainty)

Innovation

Additional Resources

Additional Images

Date submitted:

Disclaimer: The content of this practice reflects the views of the implementers and does not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations, the United Nations Network on Migration, and its members.

More Related Practices:

- Strengthening the capacities and frameworks to collect data and evidence on migration, the environment and climate change (MECC) in Mexico

- Disaggregated Data Action Plan (DDAP) - Statistics Canada

- Immigration, Refugees, and Citizenship Canada’s Use of Gender Based Analysis Plus (GBA Plus)

- Tablero Interactivo Estadísticas sobre Movilidad y Migración Internacional en México

- International Labour Migration Statistics (ILMS) Database in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) region

Peer Reviewer Feedback:

*References to Kosovo shall be understood to be in the context of United Nations Security Council resolution 1244 (1999).

Newsletter

Subscribe to our newsletter.